Moving Minorities

COVID19 & The Boy with Two Hearts by Hamed Amiri

According to the UNHCR, the number of

people forcibly displaced around the world has doubled in the past decade and

is estimated to have passed 80 million in mid-2020. Since January 1st

2021, the IOM has recorded 144 migrant fatalities worldwide with 87 of these

fatalities occurring in the Mediterranean Sea. Yet, and even closer to home,

new research from The Institute of Race Relations has revealed that in 2020 almost

300 asylum seekers including 36 children died trying to cross the Channel to

the UK in the past 20 years.

Quantitative data has the ability to group individual migrants into large homogeneous groups based on country of origin, ethnicity, cause of death, economic status, political affiliation, skill sets, means of travel, and fear of persecution amongst others. These figures are fundamental in understanding the scale of the present world refugee crisis, and they help us to compare migration today to mass exoduses of the past. However, with these figures come people; individuals with stories to tell. It is time that we listened.

Britain is often heralded as a country in which the rights and welfare of survivors of conflict and persecution are well embedded, and where the standard of living conditions of those seeking asylum is relatively high. However, the UK’s hostile environment agenda is about making borders part of everyday life. Government policy ensures that a hostile dichotomy of ‘self’ and ‘other’, that fuels anti-migrant sentiment, is entrenched within the national imagination; an ideological counterpart to the construction of oppressive border infrastructure. Yet, migrant literature can help us to re-think our moral imagination through understanding the social and personal contexts which prompt individuals to leave their homes and seek refuge elsewhere. There is a rising tide of anti-immigrant sentiment in the UK, and this often stems from hyperbolic rhetoric utilised by the Home Office, politicians and the media who market asylum seekers as economic migrants. Such rhetoric is leading UK citizens to believe that an increase in migration is putting extreme pressure on our resources such as food, housing, jobs, and social services. Dina Nayeri, author of The Ungrateful Refugee: What Immigrants Never Tell You, poignantly expresses the truth of this sentiment:

‘Unlike economic migrants, refugees have

no agency; they are no threat. Often, they are so broken, they beg to be remade

into the image of the native. As recipients of magnanimity, they can be pitied.

(...) But if you are born in the Third World and you dare to make a move before

you are shattered, your dreams are suspicious. You are a carpetbagger, an

opportunist, a thief. You are reaching above your station.’

The question is, a thief of what? The truth is, the Covid-19 pandemic has fuelled an unprecedented exodus of migrant workers that has caused the UK population to drastically drop – potentially resulting in profound damage to our economy. These men and women have helped to build the UK and to make it a better home for us all. What we are witnessing now is no migrant crisis. Arguably, in the UK at least, there never was one.

***

Have you ever visited the Serpentine Gallery in Hyde Park? This gallery was redeveloped by Dame Zaha Hadid from Baghdad. Sir Alec Issigonis from Turkey invented the Mini Cooper - one of the most productive manufacturers in the UK. Michael Marks from Belarus initiated the business and partnership with Thomas Spenser – establishing M&S. British singer Rita Ora was born to Albanian parents in Yugoslavia, now present-day Kosovo. When Yugoslavia was disintegrated, ethnic Albanians faced persecution, so her parents fled to the UK with Rita as a young child. Chelsea Footballer Victor Moses’ parents were killed when he was just 11 and he came to the UK as an asylum seeker. Ed and David Miliband, two forward-thinking labour politicians, are the sons of a Belgian Jewish refugee. Without listening to their stories, we would remain ignorant to the prosperity that migration brings. These individuals are not opportunists, but simply innovators.

***

The increasing criminalisation of immigration is established at both figurative and literal borders, which have been facilitated by the punitive expansion of control measures that illegalise people before reaching the UK. Once more, selective immigration controls (favouring those from Syria through the Syrian Vulnerable Persons Resettlement Scheme, over those from other conflict states) simply exacerbate any existing tendencies to regard certain minorities in question as ‘different’, ‘scrounges of the welfare state’, or even as ‘foreign aliens’. We need to listen to the stories of those who have made the journey here and who have experienced the journey after the journey within the UK’s asylum system. We need to hear the voices of those legally silenced, those made destitute by our own government, those left in limbo for months and even years waiting for a decision, those detained in immigration removal centres, which physically exteriorise deeper, ethnocentric cultural attitudes that criminalise refugees both in policy and language. We need to rethink our moral imagination and we can do just this by immersing ourselves in their narratives – by becoming lost in a world where they once wondered and have now been found.

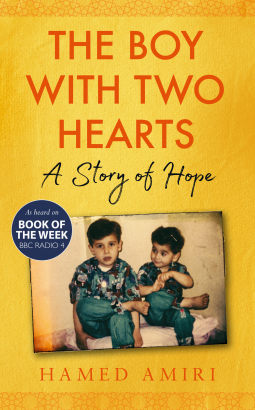

The Boy with Two Hearts by Hamed Amiri

The Boy with Two Hearts by Hamed Amiri is a tale that follows a family of five fleeing the Taliban in Herat, Afghanistan. Yet, this story is not just about persecution, fear and migration, it is also said to be but a love letter to the NHS, which gave Hussein Amiri the life-changing surgery he needed to survive. This tale is particularly pertinent to discuss at present, just at a time when Thortful (greetings card marketplace) has commissioned an initiative to encourage independent creators to create Valentine’s Day card designs to show their love for the NHS. The COVID19 pandemic has seen an increase in social solidarity with those working in hospitals, saving our lives, every day. Hamed Amiri gives acknowledgement to ‘Hannah and Beth’, two nurses who ‘loved Hussein and cared for him in so many ways’, and who later ran half a marathon in Hussein’s memory - raising over £3,000 for the NHS. In essence, Hussein’s memory now serves each and every one of us, in more ways than one.

Hamed Amiri emphasises the importance of

storytelling, as he declares in the novel’s epilogue:

‘My goal was to celebrate Hussein and

share his story with as many people as possible. […] Hussein’s story isn’t just

about our family. It isn’t even about the incredible love that underpinned

everything as we fought for freedom. It’s about a journey into hope, and love

for life even when life is hard.’

Despite the treacherous plight that the Amiri family went through on their journey to the UK and the sadness involved in losing a son, Hamed Amiri reminds us of the things that we, in the UK, take for granted - hope and most importantly, love.

It is so that Hussein left such a legacy

of love, and Hamed Amiri captures this when he describes Hussein’s first day at

university in the UK:

‘Looking around the campus that day, at

all the people from every corner of the world, it was clear they were gathered

for one thing: to follow their dreams and ambitions. I thought back on our

journey to get here, hiding in fields at night, being abandoned in jungles and

travelling in shipping containers. Hussein was just the same as any other

student now, nothing more, nothing less. He’d achieved his ambition’.

In the UK when we think of ambition, we are filled with images of the most influential authors, activists, film producers, artists, CEO’s, software developers, physicians, screen writers, and many more that go unmentioned. Hussein’s ambition to simply study is an ambition which is taken for granted in the UK. University is a natural step from school for young adults and isn’t really given a second thought. We arrive at our halls of residence without any knowledge of the person in the room next door and sometimes, we never make the time to listen to their tales of how they arrived in this location at this particular time. The message here is to simply be kind, for you never know what the ‘other’ has endured.

Hussein later became a governor for NHS Bristol, and always strived to give something back to those who endeavoured to save his life. Proceeding Hussein’s death, Hessem, Hamed Amiri’s younger brother, filled this position. The love that the Amiri family acquired for the NHS is heartening, and is made all the more poignant by the fact that they did not simply assume that they would receive the love and care that they did. Perhaps they thought themselves different to us. Perhaps they felt less worthy. But they, like us, are human beings – deserving of love. Hamed Amiri reveals that: ‘all they wanted to do was to look after my brother and make him better. Language, culture, all our stuff, didn’t really matter.’ Like COVID19, the NHS does not discriminate. The NHS saves lives. Just as Hussein was like any other student studying at university, he was also like any other patient cared for by the NHS; valued. Yet, Hussein is not like any other at all. Not a statistic. Not merely another successful asylum determination. Hussein was an individual whose life and legacy are unique. Hussein touched the souls of many here in the UK, and without the Amiri family’s migration and his living brother’s ambition to keep his story alive, we would not be reminded of the things in life that we take for granted but that are so dear to us all.

***

Refugee Tales (2016) explains:

‘Nobody leaves home for no reason. Nobody

crosses the world crushed in a crate in a lorry, drinking his own urine for

one-and-half months; nobody gets flung on a plane from one trafficking

destination to another, without terrible mental consequence’.

With this in mind, when you walk upon and witness the line of individuals and families waiting outside Lunar House in Croydon, do not discriminate, but smile and nod. Give them hope. Give them love. For they too are people just like us with stories to be shared.

***

Books recommended on the subject of migration, asylum and

persecution:

1. Refugee Tales by by Ali Smith (Author), Marina Lewycka

(Author), David Herd (Author, Editor), Chris Cleave (Author), Jade

Amoli-Jackson (Author), Patience Agbabi (Author), Inua Ellams (Author), Stephen Collis (Author), Michael

Zand (Author), Dragan Todorovic (Author), Avaes Mohammad (Author), Abdulrazak

Gurnah (Author), Anna Pincus (Editor)

2. The Lightless Sky by Gulwali Passarlay

3. The Boy with Two Hearts by Hamed Amiri

4. The New Odyssey by Patrick Kingsley

5. The Ungrateful Refugee: What Immigrants Never Tell You by

Dina Nayeri

6. The Raqqa Diaries: Escape from Islamic State by Samir

7. Violent Borders: Refugees and the Right to Move by Reece

Jones

Comments

Post a Comment